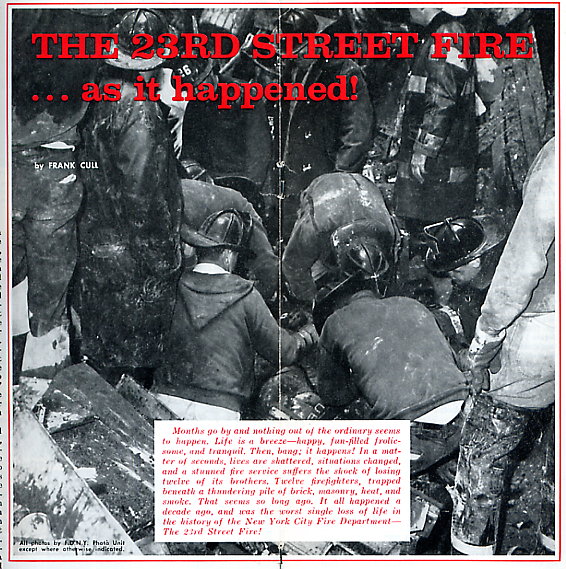

From the Pages of ...With New York Firefighters Fall 1976

It is autumn in New York and the newspapers carry a smattering of fire safety slogans. Fire Prevention Week does that-once a year, people think about the horrors of fire. Fire Prevention Week inevitably recalls America's most famous blaze, the great Chicago fire. Fire Prevention Week is always scheduled to encompass October 8th to October 10th, since 1922. At that time, the President of the United States proclaimed that week in October so that it would always be remembered with an eye towards fire prevention. You know the famous story of how Mrs. O'Leary's cow kicked over the family's kerosene lamp, touching off America's most notorious fire. Historians record Catherine O'Leary entering the barn which stabled her livestock, used in the O'Leary milk route, to get some milk for her neighbors, the McLaughlin's, who were hosting a collation. It was about 8:30 at night, and Mrs. O'Leary had placed the lamp on the floor. The cow, resenting the overtime work, kicked over the lantern, causing it to break and, allowing the spilled kerosene to ignite. Chalk one up for the cow that had overtime on her mind in 1871, for when the fire was over, one third of the city was in rubble and ruin. THE STAGE IS SET It was just one week after Fire Prevention Week in 1966, when Herbert Brown had finished reading a magazine article about the same Chicago fire. He called to his wife, "Marion, when you get a chance, read this article on the great Chicago fire." Marion Brown was in the kitchen putting the finishing touches on her neat little kitchen and looking forward to a few moments of relaxation. The Brown apartment, on the fourth floor of 7 East 22nd Street, features the ultimate in design and decor, for husband Herbert is an accomplished artist. It is now about 8:30 p.m. and, as Brown puts down the magazine, he glances at the clock noting the time; it was the same hour that the famous O'Leary cow committed her dastardly act. At the quarters of Ladder Co. 7, Lt. Finley has concluded drill time and the hustle and bustle of the East Side truck company returns to fever pitch. Over at Engine Co. 18, the phone rings and one of the brothers skips to the phone and answers, "You light 'em, we fight 'em!" with that firehouse humor that sustains the men of the fire service. "Is John Donovan there?" queries the caller on the other end. "No he's not. He's out of quarters on tag summons duty," comes the reply. At headquarters of the 3rd Division, which is nestled between a myriad of spiraling glass and steel complexes, Chief Tom Reilly, a gray-haired man with a pleasant personality, shuffles some Department papers and hands the "orders" for that day to his aide, Bill McCarron. "Too bad the Department can't figure some way to use all this paper to put out a fire," quips McCarron, as he gets "the papers" ready for all the units in their midtown Manhattan division. McCarron, a World War II vet, has been with Chief Reilly for five years now, starting out in the 7th Battalion in 1961. Appointed on June 16th, 1953, McCarron served with Engine Co. 26 before moving to his new post as Aide to the Chief of the 7th Battalion, Tom Reilly. McCarron, short in stature but big in heart, has a reputation that to know him is to like him. Chief Reilly, a seasoned veteran, was appointed January 1st, 1937, and assigned to Engine Co. 29. After that, he did short stints in Ladder Co. 17, and as an aide to Chief Bettex in the 10th Battalion. Promotion to Lieutenant (1943) brought him to Engine Co. 37. In 1948, Reilly got his "railroad tracks" and skippered Engine Co. 246, and Engine Co. 40. In 1954, he was promoted to Battalion Chief and assigned to the 7th Battalion and, in 1963, he attained his current rank of Deputy. Over at Battalion 7, Battalion Chief Walter Higgins is kidding his aide, Howie Bowe, about taking military leave. Both men hold officer's ranks in the military, Bowe in the National Guard, and Chief Higgins in the Naval Reserve. Higgins, a tall, thin man on the quiet side, is in excellent physical shape. An exceptional administrator and fire officer, he is also a lawyer and was appointed on July 1, 1942. Walter Higgins had served as a firefighter in Ladder Co. 22 and, in 1953, moved over the Ladder Co. 2 as a lieutenant, and then to Engine Co. 21. From Engine Co. 21, he was "upped" to Captain and moved crosstown to command Ladder Co. 21. That unit did pioneer work under Higgins in the use of the ladder pipe and, as a result, Evolution No. 21 (Metal Aerial Ladder As Water Tower) was numbered in their honor. In 1962, Higgins  was assigned top the 7th

Battalion, having attained the rank of Battalion Chief. was assigned top the 7th

Battalion, having attained the rank of Battalion Chief. BUSINESS AS USUAL Back at 22nd Street, three truck drivers bounce into a local bar from the trucking concern around the corner. The bar is on the ground floor of number 9, the building adjoining 7 East 22nd Street. The cellar is used by an art dealer. Around the corner, the street front of 6 East 23rd Street is divided into three occupancies: Wonder Drugs, Fan's Lingerie Shop, and a Barricini's candy shop. Access to the cellar could only be had through an interior stairway in the Wonder Drug Store. The width of the cellar area occupied by Wonder Drugs is approximately the width of the building. The length of the cellar area had been diminished by the erection, without application, permit, or building notice, of two cinder block partitions; one of which had been arched. The resulting situation created a deceptive picture which would lead an inspector to believe that he had inspected the entire cellar of 6 East 23rd Street when, in point of fact, an additional area, thirty-five feet in depth, existed behind the southernmost cinder block wall. At the time of each inspection, the occupants of Fan's and Barricini's advised the inspector that they had no cellar occupancy, and no interior cellar entrance. It should be noted that there was no entrance to the cellar of 6 East 23rd Street from the street, nor was there any interconnection on the first floor level of the buildings at 6 East 23rd Street, and 7 East 22nd Street. The interconnection on the second floor was unorthodox. The doors between the buildings gave the impression of closet space rather than access doors, and contributed to the lack of recognition of it being a single building. This maze-like setup prevented any early discovery of the blaze that was said to have originated in the cellar portion used by the art dealer. The bar is alive with the sound of chatter, laughter and a tinkling of glasses. Several patrons are being served dinner. Idle chatter permeates the cigarette smoke with discussions of Lee Marvin and "Cat Ballou", the "Sound of Music", Elizabeth Taylor, and President Johnson and Lady Bird. The three truck drivers, Jim Harris, Knobby Walsh and Hank Slovich are in a heated debate about football. It's a "who's better"-Johnny Unitas or Bart Starr-gridiron battle. Walsh's beer goes down with a smoothness that delights his thirst after a hard day's work. Harris is a big man with a laugh that makes everyone happy. Hank Slovich kids the other two lads about drinking, while he puts away few "boilermakers." The restrooms and kitchen are both close to the point where the fire originated, but neither customers nor employees detect anything being wrong. The forty inch thickness of the adjoining brick walls of the two buildings prevented both heat and smoke from penetrating from the art dealer's cellar to the bar. Similarly, the unusual five inch thick concrete floor of both the art dealer and the drug store diverted the normal path of smoke, heat, and fire. THE FIRST SIGN Upstairs, Marion Brown smells smoke. "Honey, do you smell something burning?" Herb Brown jumps from his seat, abandoning the basketball game on T.V. Quickly he searches the apartment and finds nothing wrong. "Maybe you have the Chicago fire on your mind," he calls to his wife. He sits down, but within minutes decides to take another look around. He goes down to the third floor, ten to the second. Suddenly, the realization that something is wrong! He thinks to himself, "Where is this odor coming from?" He races back to the third floor and looks out on a two story extension that connects the 22nd Street side of the building with the 23rd Street side. He looks out on a sight that sends a shiver throughout his body. His eyes mirror something that he does not want to see. Thick, greyish-black smoke pulsates from the top of the roof and skylight of the extension with a rhythmic beat, almost to the tempo of a drummer. Brown turns and races for his apartment. Dashing into the  apartment, he screams to his wife, "Call the Fire

Department," and continues to the bedrooms. He

awakens his four children and, without trying to frighten

them, quickly dresses them. "Just a precaution,

Marion," as he buttons up the little one. "The

firemen are on the way," his wife retorts. Within a

few seconds, thick, black smoke fills the apartment and

the lights go out. Suddenly, they're confronted with a

whirling of black poison. Brown huddles the family

together and, in chain-like fashion, they make their

escape from the building. Herbert Brown is trembling,

beads of perspiration glisten on his forehead. The family

breathes in the autumn air that now seems to be

spring-like. "Thank G-d we're out," whispers

Marion as she huddles her little family together.

apartment, he screams to his wife, "Call the Fire

Department," and continues to the bedrooms. He

awakens his four children and, without trying to frighten

them, quickly dresses them. "Just a precaution,

Marion," as he buttons up the little one. "The

firemen are on the way," his wife retorts. Within a

few seconds, thick, black smoke fills the apartment and

the lights go out. Suddenly, they're confronted with a

whirling of black poison. Brown huddles the family

together and, in chain-like fashion, they make their

escape from the building. Herbert Brown is trembling,

beads of perspiration glisten on his forehead. The family

breathes in the autumn air that now seems to be

spring-like. "Thank G-d we're out," whispers

Marion as she huddles her little family together. ALARM RECEIVED Manhattan Communications records the call from Marion Brown at 9:36 p.m. In a matter of seconds, units of the New York City Fire Department are out of their fire stations and rolling to Box 598. Engine Companies 14, 3, and 16, along with Ladder Companies 3 and 12 roll in. Fourteen Engine swings into the block with the firefighters clinging to their red fire engine. The men on the back step peer out on one side to see if they can see anything. "Nothing showing," one number of the unit shouts to the others. The extension, from which Mr. Brown saw smoke emanating, was shielded on all four sides by taller structures, preventing passersby from seeing any smoke. Battalion Six pulls up and Battalion Chief Frederick White springs from his car, sensing a "worker." Deputy Chief Reilly also arrives at 7 East 22nd Street and is confronted with a serious cellar fire. When examination reveals that immediate extinguishment of the cellar fire is not possible, he follows the basic principles of fighting cellar fires and attempts to control the first floor to prevent extension to the upper floors. As heat conditions intensify in the cellar, he withdraws his forces from that area and concentrates his efforts on the control of the first and higher floors, while making provisions for the examination of the exposures. He is handicapped by a lack of information regarding this building's construction, alterations, arrangements, interconnections, extensions and occupancies. The extension between the wings of the buildings deprives him of an access to the rear of either wing, and seriously interferes with his reconnaissance. In the meantime, Chief Reilly, quite reasonably, is protecting what he considers to be a completely separate building: 6 East 23rd Street. The heat and smoke conditions on the first floor are similar to those associated with seepage, and give no indication of fire extension. First due units immediately begin their attack on the fire. The origin of the blaze is not evident. At 9:58 p.m., Chief Reilly sends in the "all hands." All hands at work at Box 598 requires the additional response of Rescue Co. 1, and the 7th Battalion. "Let's go, Howie," says Higgins as he turns to his aide. "They've got something going at five-nine-eight." UNITS SPECIAL-CALLED Chief Reilly figures that he needs another truck company to direct a stream from the street into the upper floors, and shouts to Aide McCarron, "Get us another truck, Bill." "Division Three to Manhattan," starts the radio message that will bring out Ladder Co. 7. At 10:03 p.m., a special call goes out to bring Ladder Co. 7 to the scene. Lt. Jack Finley and his troops, knowing that the "all hands" was in, had been glued to the Department radio listening to the voice of Bill McCarron giving a progress report. Having kept themselves apprised of the changing situation, the men of Ladder 7 know that this is a bad one. The bells ring in a quick "seven" followed by a pause, and then a "five-nine-eight" followed by still another pause, and another quick "seven." The bells seem to bang in with a sense of urgency. The brothers kick off their unlaced shoes and don their boots; then their black rubber coats with the zebra yellow stripes and finally their helmets.  Lt. Jack Finley, the officer for the tour, jumps up into the front seat and turns to check for his tillerman. Finley, appointed on May 1, 1937, has an Irish way about him, and is well liked and respected by his troops. As a firefighter, he served with Ladder Co. 136, Ladder Co. 2, and Engine Co. 251. On November 11, 1962, he was sworn in as a lieutenant and, after a year of "covering" in the 1st Battalion, hangs his helmet in Ladder Co. 7. Finley looks around once more and sees that Jack Berry, Rudy Kaminsky, and Carl Lee are ready to roll. The trio, all over six feet in height, are an impressive sight. John Berry, appointed on Sept. 16, 1961, has spent all of his time with the men of Ladder 7. Only a few months before, he had moved his family to Long Island. Carl Lee was appointed on November 29 1960. After a training school stint with Chief Kehayas, Lee came to Ladder Co. 7 on February 11, 1961. Rudolph Kaminsky came to the F.D.N.Y. from Astoria. Rudy was sworn in on June 14, 1958, and his personnel folder shows service in the Korean war. After five years in Ladder Co. 7, he transferred to Ladder Co. 22, and then to the 11th Battalion (Aide to Chief Maly). In 1965, he returned to Ladder Co. 7. Eighteen Engine is a long narrow firehouse, located on West 10th Street. The troops, there too, are gathered around the housewatch desk. Jimmy Galanaugh turns to Monsignor Jablonski, "That's a bad box, father." Monseignor Jablonski is in quarters on a spiritual and social call; part of his duties as one of the Department's Chaplains. Galanaugh, with a look of concern, waits for the Chaplains reply. Before Father Jablonski can answer, Joe Kelly turns, flashes his familiar smile, and says, "Nothing to worry about, gentlemen. Ladder Co. 7, the pride of the East Side, is on the way." Six minutes later, they too will be on their way to the fire. With units reporting back to Chief Reilly's command post that they are encountering increasingly heavy heat and smoke conditions, and little success in locating the main body of fire, Deputy Chief Reilly transmits a second alarm. Two quick bells sound at "18," and before the rest of the signal can come in, the housewatchman hells, "We go." The adrenalin starts to flow, and the noisy Mack pumper starts to "rev up." Lt. Priore checks his light and watches Daniel Rey put on his turnout coat. Priore is a covering lieutenant and Rey, a proby. Both wear a look of apprehension and loneliness. And both, deep down, feel a sense of eagerness. Both are new in their jobs; they want to be accepted. Priore, a gentle, pleasant man was appointed in 1953. A World War II vet, he came on the job late in life. As a firefighter, he served with Ladder Co. 128 until 1966 when he was elevated to the rank of lieutenant. He lives in Astoria, not far from Rudy Kaminsky of Ladder Co. 7. The crew, Bernie Tepper (appointed August 1, 1963), Jim Galanaugh (appointed February 10, 1962), Joe Kelly (appointed February 20, 1960), and Dan Rey (appointed June 11, 1966) are young, but experienced. All four have called 18 Engine their home since they entered the fire service of the City of New York. The neighborhood of Madison Square Park has picked up the tempo of a multiple alarm fire. Red lights flash, sirens wail, hose is stretched, aerial ladders move skyward, and units go to work. SUDDENLY A COLLAPSE The fire is gaining headway as Chief Allen Hay (Division 1) rolls in, followed by Assistant Chief Harry Goebel. Chief offices are assigned to exposures with explicit orders to intensify their search for the main body of fire.

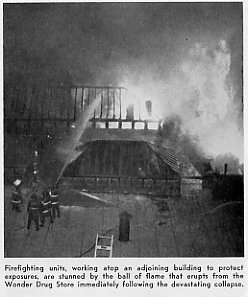

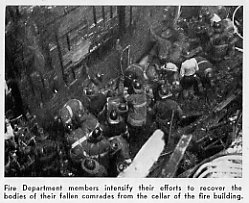

Engine Co. 5 and Ladder Co.3 are operating in the cellar of the drug store (6 East 23rd Street). Engine Co. 18 and Ladder Co. 7 are right above them, operating in the rear of the drug store. All four units are supervised by Chief Higgins, while Reilly makes his way to the roof for more reconnaissance. As the Deputy readches the roof area he can see, from his lofty perch, that the fire has extended via a shaft between the building around the corner (7 East 22 Street) and the large corner building (940 Broadway). "Uh, uh. Now we really got problems," thinks Reilly as he contacts Chief Goebel on his radio pak set and reports conditions. Goebel requests a third alarm assignment. In the cellar, Captain Pat Murphy, of Engine Co. 5, calls to Firefighter Cicero. "Hey, Nick. Go up to the top of the stairs and keep an eye on things." Cicero climbs to the head of the stairs and, while manning his observation post, clears away some stock that is piled near the door. A similar thought comes across the mind of Chief Higgins. He turns to his aide, Howard Bowe. "Howie, go down to the cellar and let us know what conditions are like with 5 and 3." Higgins is sending Howie Bowe on a mission that will spare his life. At the stairs, which are near the front of the store, Cicero is startled by a cardboard box that flies across the first floor, hurled through space by some seemingly supernatural force. It is accompanied by a large-scale air movement. Firefighter Breetveld, of Ladder Co. 3, enters the drug store to rejoin his unit, and is met with a tremendous heat wave. Swirling black smoke gushes towards him and forces him into a hasty retreat, his neck burning. Cicero had called to the skipper of Eng. 5, "Cap, there's something wrong up here." The men in the cellar begin an orderly withdrawal, taking their equipment with them. Nick Cicero starts to look around, and screams a warning towards the rear of the store. His warning to Higgins and his men goes unheard. The enginemen in the rear are operating, and their powerful stream of water has drowned out any noise. The glare from Higgins' light bounces from the surface with drops of water glistening between the rays. It's the last thing they will see. Cicero's warnings are further impeded by the partition that encloses the top of the staircase, and the difference in depth between the cellar and the first floor of the Wonder Drug Store. Cicero is now on his knees, shouting into the cellar, "Dammit! Get out, get out"-his voice, screaming, rises to a fever pitch. The men below sense the fear in Nick's voice and begin a hasty retreat. Hurriedly, they climb the stairs. They crawl from the store, screaming, burning, pulling each other from the superheated atmosphere. Fear is etched across their brows, and their faces are ashen white. It's 10:39 p.m., and it happens. A tremendous roar, and a collapse that unleashes a flaming fury of bricks, mortar and heavy timbers. The men fall like puppets that have had their strings cut. They fall with startling suddenness; and the building comes crashing down on top of them. BLAZE CONCEALED A strange set of circumstances had been initiated due to the fact that the firefighters were unaware that this building ran from street to street. A four-inch thick cinder block partition wall, erected in 1960 by a previous owner, had cut the length of the cellar. This wall separated the diminished area of the druggist's cellar from the area used and occupied by the art dealer. The druggist, therefore, occupied a store that was one hundred feet deep, and a cellar that was only sixty-five feet deep. Conversely, the art dealer's cellar extended one hundred and thirty-five feet from 22nd Street, with the northernmost thirty-five feet beneath the drug store. Thus, the firefighters sent to the cellar to check for the fire, saw very little evidence of the blaze that was raging on the other side of the wall. The twelve men on the first floor were standing on a floor made up of five inches of concrete and asphalt tile, and were situated over the main body of fire.  The evidence of maximum burning indicated that the fire had burned for a considerable period of time in the first floor construction, between the metal fire-retarding cellar ceiling cover and the unusual insulating layer of concrete at the first floor level. These conditions were ideal for a buildup of intense heat, as found in a "firebox." These heavy timbers, used in the construction of this area, require very high temperatures, over a considerable period of time, to have burned and charred into the condition noted on exposure. With the loss of support on one end, the beams were pulled completely out of their wall sockets on the opposite end. The section of flooring, being supported by these beams, collapsed with suddenness difficult to comprehend. The ten firefighters were hurled to their deaths, with no warning or indication, whatsoever, of the raging inferno that blazed beneath. McCarron and Kaminsky were killed on the first floor, at the very edge of the collapsed area. THE GRIM SEARCH Chief Hay is next door in the lingerie store at the rear, just a few feet from the collapse. The force from the collapse flattens him, and clouds of dust engulf him. He staggers to the street and finds the ten firefighters who made their escape from the cellar sprawled all over the sidewalk. The fire has broken through in the rear, and everything is a mass of flames. The pent-up flames have finally burst from their hiding place. On the 22nd Street side, units had received more warning. They had been met with the same searing heat, but had also heard some rumbling noises that gave them that warning. Several of these firefighters were burned about the face as they made their way out. Third alarm units are arriving. Chief Hay immediately organizes all the available forces in front of the building, and lines are stretched to drive back the flames in order to reach the trapped men. The first unit stretches in and the fire flares up in the front of the store, temporarily trapping them in the rear. A back-up team moves in with another hoseline and knocks down that body of fire. Each man in the rescue party is pushing himself beyond the limits of sheer physical endurance. They all echo the same thought, "We've got to get to them." John Donovan arrives at the scene. Donovan had been out of quarters on tag summons duty. Learning that the men of "18" were trapped, he races into the building to help push the line ahead. In complete darkness, the rescue party, undaunted by the surroundings, moves forward. Unbeknown to them, they have reached the area of the collapse. Donovan is now the nozzelman and, as he crawls forward towards the orange glow, he plunges over the edge of the collapsed area. John Donovan dangles over the open pit, clinging to the nozzle. His life passes in front of him, and he knows now that he has found his brothers from 18 Engine. He sways back and forth, like the pendulum of a clock, desperately hanging on to the controlling nozzle. His hand is slipping and his turnout coat is starting to burn, when a guardian angel in a rubber coat reaches for him. Then comes hand after hand, to pluck him from a fiery death in the flaming ruins. Donovan is dragged to the street in shock. He cries out in a remorseful tone, "Please, G-d." Manny Fernandez comes over to comfort Donovan. Fernandez is the motor pump operator for Engine 18, and he trembles at the thought that John and he are the only ones left. Francis Love responds and takes command of the fire. Chef Love orders a fourth alarm to cope with the complex problems being presented in both rescue and firefighting operations. At 11:28 p.m., a fifth alarm is transmitted. Three major collapses and a series of minor collapses has hampered all efforts. Fire Commissioner Robert Lowery stands forlornly in front of the building. His eyes reddened, \he peers sadly at what is before him. Mayor John Lindsay arrives. Chief of Department John O'Hagan arrives. O'Hagan was in Chicago when the blaze erupted and, after being informed of conditions, flew back to the City and was rushed to the scene.  At

one time, hope was held that the trapped men might have

found refuge. "Tappings" from the basement were

heard, but investigation disclosed that the noises heard

were only exploding bottles in the superheated cellar of

the burned out drug store. At

one time, hope was held that the trapped men might have

found refuge. "Tappings" from the basement were

heard, but investigation disclosed that the noises heard

were only exploding bottles in the superheated cellar of

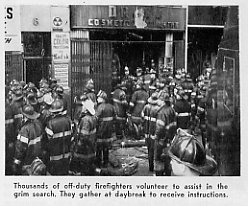

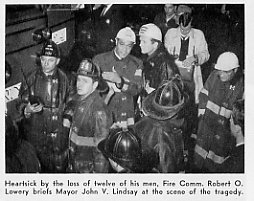

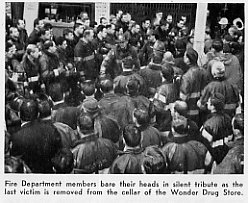

the burned out drug store. TEARS AND BROKEN HEARTS The bodies of Bill McCarron and Rudy Kaminsky, both of whom are found on the first floor, are removed around 1:30 a.m. The attempt to reach the bodies of the ten firefighters in the cellar continues. Two thousand off-duty firefighters respond to the scene in an effort to help with the search. As time drags on, the reality of it all surfaces-all is lost! A crowd of several hundred people watch in grim silence as searchers continue to probe the ruins. Fire Patrolman Edward Pospicil, who had noticed the missing units at work while going about his own duties, draws a map for the search parties. The sketch is of invaluable aid in locating the trapped victims. Mayor Lindsay dons turnout gear to make an inspection. A minor collapse takes place, narrowly missing him. He quickly emerges and turns to a reporter, "I'm heartsick. It's very grim. It's terrible in there. The heat and smoke are awful." A firefighter standing nearby thinks to himself, "The heat and smoke are always awful-every day." The early hours of the morning will unveil twelve tragedies. At the home of Daniel Rey, the family has gathered. Dan's father, a thirty-year veteran of the Department, stands stunned. Dan's brother, Tom, is also a firefighter. His mother, Josephine, and his wife, Virginia, get the bad news. Dan was one of the victims. He had enjoyed a total of three weeks of active duty. Winifred McCarron knows that she is a widow. She sits quietly in the waiting room of the City Morgue waiting for her brother-in-law, Joseph McCarron, to identify the body of her husband. A rugged homicide detective stands holding a grocery list, and a list of school supplies recovered from the pockets of the dead. He quietly thinks to himself how in the other organizations the bosses stand back and send the troops in; but not here. It's a team effort, regardless of rank. He shakes his head with a sincere gesture of admiration and mumbles, "My G-d, I have children of my own. I'll never get over it." Pieces of the charred papers float out of his hand-he reaches-they're gone! The last body is removed as several hundred tired, beaten, firefighters exit from the blackened brick and steel tomb, and slowly make their way across to Madison Square Park. Chief of Department John T. O'Hagan begins to speak. The men remove their helmets and gather around him. He speaks of their twelve comrades and the silent men listen. "This is the saddest day in the one hundred year history of the Fire Department. They never had a chance. I know that we all died a little in there." O'Hagan thanks the men for their superhuman efforts and ends the impromptu memorial service by asking the firefighters to observe a moment of silent prayer. Monsignor Merritt Yeager is sent to 37th Street in Astoria. In a career that will span forty years as a Fire Department Chaplain, Father Yeager will make this trip alone many times. He climbs the steps and rings the doorbell in the dead of night. Jeanette Kaminsky is startled and, half awake, goes for he front door. She looks through the curtains and seeks a man standing on the stoop. He has a flashlight and shines it up towards himself. Her body goes limp. She sees the Roman collar-she knows it's Father Yeager.  The

same events are taking place in Springfield Gardens. Here

it's Ann Kelly, and Rev. Dr. Fred Eckhardt, a Protestant

Minister. Eckhardt is also a Fire Department Chaplain.

Mrs. Joseph Kelly begins to sob. After a while, she tells

Rev. Eckhardt that she and Joe were planning to celebrate

their 15th wedding anniversary next week. The

same events are taking place in Springfield Gardens. Here

it's Ann Kelly, and Rev. Dr. Fred Eckhardt, a Protestant

Minister. Eckhardt is also a Fire Department Chaplain.

Mrs. Joseph Kelly begins to sob. After a while, she tells

Rev. Eckhardt that she and Joe were planning to celebrate

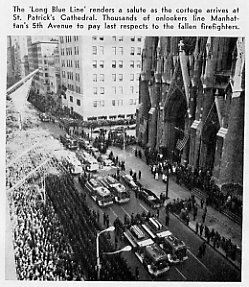

their 15th wedding anniversary next week. Ginnie Galanaugh is at the scene. She knows the answer to her question as she turns to Tony Liotta, a member of her husband's company. "He's alright, isn't he?" Instead of answering, Tony embraces the young woman. "Oh, no," she cries out. "Not again." Her father had made the supreme sacrifice in 1955, and now her husband. James Vincent Galanaugh, an eleven-month-old boy, is at home with his grandmother. The toddler will go through life proudly bearing the names of his father and grandfather; both heroes who met their demise battling the ravages of fire. Ethel Finley is on the phone and the doorbell rings. She runs, sobbing to the door. On October 14, she and John Finley had celebrated their thirtieth wedding anniversary. Now, three days later, their marriage died in the fire. Marie Reilly, Dorothy Tepper, Marjorie Berry, Betsy Lee, Grace Priore and Virginia Higgins are all suffering the same pain and anguish. Twelve widows and their thirty-six children, living with the thoughts of their loved ones, drawn together by the closeness that binds one firefighter to another. These people, who live under the swaying sword of Damocles, living with the knowledge that death is a routine part of their jobs. THE NEXT DAY The sun is shining the next morning as Captain Karl Kortum walks slowly into the quarters of Engine Co. 18. Ashen faced, his blue work uniform is caked with soot and his hands are shaking. Kortum was scheduled to be on duty the previous night, but Lt. Priore had worked a mutual for him. Gazing through bloodshot eyes, and totally fatigued from many hours at the fire scene, he leans forward and removes four names from the duty board. He looks down at the name cards he just removed and starts to speak, but his voice cannot express the feelings in his heart. His eyes fill, and he abruptly turns and walks away with the shuffle of a man who has lost too much. Now it's nighttime and Ben Messina, an official with the Uniformed Firefighters Association, makes his way towards a neat split-level home in Baisley Park, Queens. Messina is there to talk to the widow of Bernard Tepper about funeral arrangements. As he makes his way to the house, his mind is racing to help him with some thoughts on what he will say. A youngster startles Messina with, "Are you a fireman?" "Yes, I am," replies Ben. "Were you saved?" is the youngster's next question. Messina looks away and doesn't answer. Bernard Tepper's son is too young to fully understand what has happened, but he knows that his daddy won't be coming home from the firehouse anymore. A message from the London Union of Fire Brigades asked that "our complete sympathy be extended to the families of your unfortunate brothers." A little girl walks fourteen blocks to make her small contribution to the fund for the firefighters' children left fatherless. She said at City Hall, "I didn't want to waste a nickel on buying a stamp." The fund will reach the unbelievable amount of nearly $700,000.00. THE LAST SALUTE On October 21st 1966, New York City's Fifth Avenue becomes a "sea of blue," as firefighters from all over the world come to pay their respects to the twelve brothers who had answered their last alarm. On Madison Avenue, a long block away, the tolling church bells are heard, but people go about their business, seemingly oblivious to the tragedy and the reverence. Each firefighter, standing at attention, was equally oblivious to the rest of the City. Their hearts, their tears and their thoughts were with their twelve comrades. They are surrounded by their colleagues, their brothers, their own-and they understand, better than anyone else, what this is all about! Pumper after pumper rumbles down the avenue. These same pumpers that brought these brave souls to their jobs of fire, is now taking them to their final alarm. All are greeted with snappy salutes. The cortege stops at St. Thomas' Episcopal Church for the four Protestant fire heroes, and then a St. Patrick's Cathedral, where Francis Cardinal Spellman prepares to celebrate a Requiem Mass for the six Catholic men. One Staff Officer remarks, "In March they were here for the St. Patrick's Day Parade, and in April for the Holy Name Mass and Communion Breakfast. And now...." his voice trails off.  Out

on Long Island, the two firefighters ho responded from

the 3rd Division will have funeral services conducted at

Catholic churches near their respective homes. Deputy

Chief Reilly's is being conducted at St. Brigit's in

Westbury, and Firefighter William McCarron's at St.

Boniface in Elmont. Out

on Long Island, the two firefighters ho responded from

the 3rd Division will have funeral services conducted at

Catholic churches near their respective homes. Deputy

Chief Reilly's is being conducted at St. Brigit's in

Westbury, and Firefighter William McCarron's at St.

Boniface in Elmont. American flags drape all the caskets except those of Firefighter John G. Berry and Lieutenant John F. Finley, the only two of the dead who were not veterans of the Armed Forces. Their caskets are draped with the red and white official New York City Fire Department flag. An elderly woman watches the funeral procession move slowly by. She is crying. "You hear about these things, you even see them on television. But they're not real. Not at all real, until all of a sudden there is this." She gestures toward the ten pumpers with their pathetic burdens and turns away sobbing, "What find men!" THE PAIN IS STILL THERE Five years later, memorial services were held at the site of the fire. The block-long scar of gutted buildings at Broadway and 23rd Street have been healed by bulldozers. Fire Chief O'Hagan stands and stares at black asphalt, white lines, yellow lines, and chain fencing-a parking lot for a monument! He senses an empty feeling in his stomach. So does Firefighter Ralph Feldman, who is also attending the memorial services. The pain cannot be covered over. Neither man likes what he sees. The thoughts of both men drift from the setting. They remember how the media covered the story; they remember the speeches and they remember how the widows had to return home to continue living. There must be more! THE ETERNAL FLAME  The

years fly by, and suddenly it's 1976 and the nation is

singing "Happy Birthday" to itself. On October

17, 1976, the Fire Department of the City of New York

returns to 23rd Street for memorial services. A bugler

stands at the ready. Men with the pipes and drums of the

Emerald Society Bagpipe Band stand out in their crimson

jackets. Mourning purple and black bunting flutters in

the breeze. The Mayer is there. So is John T. O'Hagan,

now the Fire Commissioner. Commissioner O'Hagan announces

that twelve streets at the brand new Fire Academy on

Ward's Island will be named in honor of the fallen men.

Reilly Boulevard, McCarron Drive, Higgins Avenue, Finley

Place, Priore Road, Berry Place, Galanaugh Lane, Kaminsky

Road, Kelly Street, Carl Lee Place, Tepper Avenue and

Daniel Rey Square will make for a fitting tribute with

the respect and dignity that these men deserve. They will

be remembered! The

years fly by, and suddenly it's 1976 and the nation is

singing "Happy Birthday" to itself. On October

17, 1976, the Fire Department of the City of New York

returns to 23rd Street for memorial services. A bugler

stands at the ready. Men with the pipes and drums of the

Emerald Society Bagpipe Band stand out in their crimson

jackets. Mourning purple and black bunting flutters in

the breeze. The Mayer is there. So is John T. O'Hagan,

now the Fire Commissioner. Commissioner O'Hagan announces

that twelve streets at the brand new Fire Academy on

Ward's Island will be named in honor of the fallen men.

Reilly Boulevard, McCarron Drive, Higgins Avenue, Finley

Place, Priore Road, Berry Place, Galanaugh Lane, Kaminsky

Road, Kelly Street, Carl Lee Place, Tepper Avenue and

Daniel Rey Square will make for a fitting tribute with

the respect and dignity that these men deserve. They will

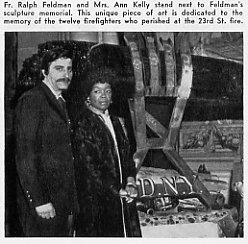

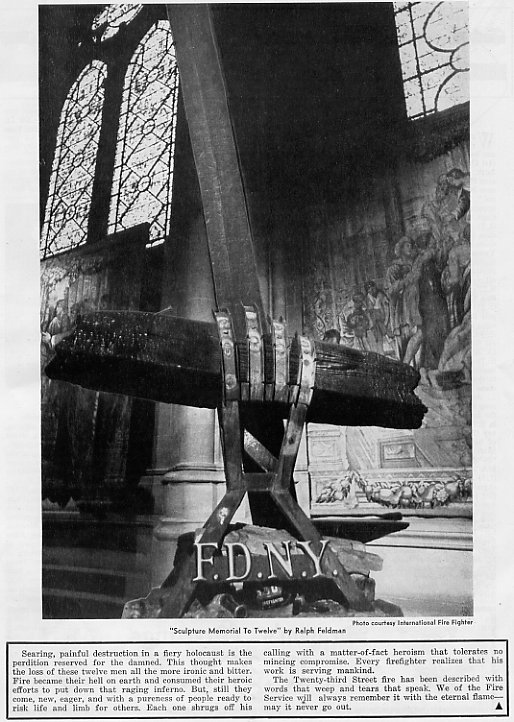

be remembered! Ralph Feldman has also done his thing. He has reached into his heart and thoughts and created a monument-an eternal remembrance for the 23rd Street victims. Feldman, of Engine Co. 37, has a wealth of talent in art and sculpture. He also holds an engineering degree from C.C.N.Y. The gang at Engine Co. 37 and Ladder Co. 40 offer to help. The construction of the sculpture comes easy to Ralph. The memorial is fashioned together with burnt wooden beams, bricks that have been charred from red to black, and scorched metal. All the pieces come from debris gathered at the scenes of actual fires. The men in the firehouse are amazed at the end result; A thirty-foot charred beam, grasped at the cross beam by a skeletal band of steel. "It never occurred to me that I was building a sort of cross," says Feldman. "But, obviously that's what we have here." Now comes the hard part for the firefighter-sculptor. "Where to put it," exclaims Feldman. His idea of installing it at the site of the fire is rejected by the owners at 23rd Street. One night in the firehouse kitchen, someone suggests, "Hey, Ralph, why not a church?" The Very Reverend James Morton and Father Richard Mann, of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, are impressed with the sculpture, and the spirit in which it was created. The monument is permanently installed in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. A ceremony is held and the candles in the Cathedral flicker in eternal vigilance. The monument has found a place in G-d's house. Ralph Feldman can be truly proud-They Will Be Remembered!

|

| Return to 8TH STREET SHUL Home Page |